The Greater Chicago Food Depository’s colorful 40-year history began with six people and a dream.

Each of the six founders – Ann Connor, Rev. Phil Marquard, Thomas O’Connell, Gertrude Snodgrass, Bob Strube, Sr. and Ed Sunshine – brought unique skills and experiences to the mission.

Their collective dream was to find a more systemic way of feeding people facing hunger in the Chicago area. Over a series of meetings – and inspired by the nation’s first food bank in Phoenix – they sharpened the vision for a nonprofit that would better connect food companies to the food pantries and soup kitchens throughout the city.

From one of Strube’s produce stalls in the once bustling South Water Market, the Food Depository began distributing food in 1979 with only two full-time employees, one part-time secretary and no guarantee of success.

The fledgling food bank movement had officially arrived in Chicago.

In the beginning

“We started with virtually nothing. … It was a 12-hour-a-day, six-or-seven-day-a-week monster job, very all consuming, completely open-ended. You couldn’t do enough,” recalled David Chandler, 70, the Food Depository’s first executive director.

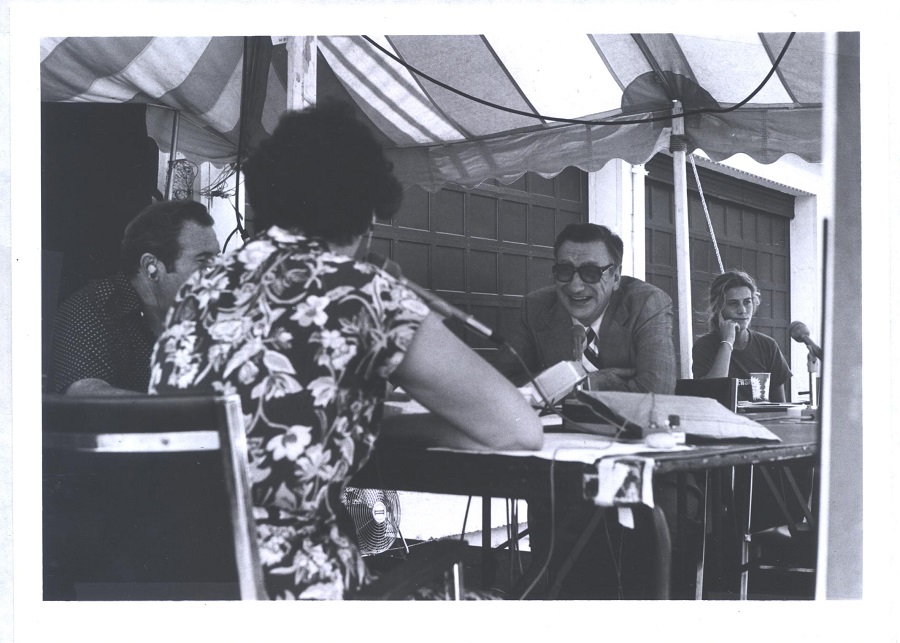

David Chandler was the Food Depository's first executive director.

Chandler, a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, had spent most of his 20s doing charity work on Chicago’s North Side, connecting people to welfare and running the food pantry at St. Thomas of Canterbury Church in the Uptown neighborhood. Chandler was looking for a way to help a broader swath of people. He was 29 when he became the Food Depository’s executive director.

Leah Kranz, the other full-time employee as the Food Depository’s assistant director, was at the time a 36-year-old single mother of five young children. She had been working in sales when she learned about the job opening through her church, Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church.

“I was really drawn to the mission, partly because I knew what it was like to be a single mom and supporting five children,” said Kranz, who would eventually succeed Chandler to become the Food Depository’s second executive director.

Together, Chandler and Kranz worked long hours to grow the food bank, assisted by a dependable cadre of volunteers, many of them employees of Strube’s wholesale produce business. With Chandler largely focused on operations, Kranz used her sales experience to raise money and solicit food donations.

In its first year, the Greater Chicago Food Depository distributed 500,000 pounds of food to 85 agencies serving 50,000 people, according to the annual report. By the second year, all of those figures had more than doubled.

By 1983, the Food Depository was distributing 11.2 million pounds of food to 525 agencies serving 500,000 people.

“When we started the food bank, we realized if this works, it would become an important institution for the city,” Chandler said. “We were building something.”

None of that would have been possible without the six founders.

“The Food Depository would never have been launched without this group of people who were really dedicated and who really put in time,” Chandler said.

‘A path forward’

Bob Strube, Sr. wanted to do more than just sell produce, his son said. He wanted to eliminate hunger.

“That was his goal. … My father was always interested in feeding hungry people,” said Bob Strube, Jr., who’s now retired from the family business, Strube Celery & Vegetable, founded in 1913.

Bob Strube, smiling on right, was one of the Food Depository's six founders. Strube, a well-respected produce wholesaler, helped draw attention to the cause with his larger-than-life personality.

A well-respected man on the South Water Market with a booming voice, Strube sought to raise the profile of the company in order to have a larger social impact. He’d make frequent visits to City Hall and hobnobbed with various mayors and other dignitaries. He wanted to be part of the social fabric of Chicago.

“He used to tell me, ‘If you get into a row boat and try to go across Lake Michigan, it’s not too easy to do. But if you go with your neighbors and friends, it makes it a lot easier to row the boat,’” Strube, Jr. said.

Strube, who died in 2010, was also part of what Chandler described as “an ecumenical movement” among faith leaders of different denominations to unite in a larger-scale effort to end hunger. Strube, active in his Lutheran church, was also chairman of a committee on hunger for the Church Federation of Greater Chicago.

Father Phil Marquard – a Franciscan priest described in a 1988 Chicago Tribune story as a “lifelong champion of the poor, hungry and homeless” – connected several of the founders who were part of the Third Order of the St. Francis, a Catholic order of laypeople. It was Marquard and Tom O’Connell, according to the Tribune story, who attended a conference in Minnesota where they learned about the first food bank in Phoenix, Arizona, which was founded by John van Hengel.

From there, Marquard arranged a meeting with van Hengel and three of the other founders: Strube, Gertrude Snodgrass, who was also a member of the Third Order of St. Francis, and Ed Sunshine, a former Jesuit priest who had left the priesthood and married Ann Connor in 1977.

“That gave us an idea of what could be done,” Sunshine recalled of the meeting with van Hengel. “It showed us we had a path forward.”

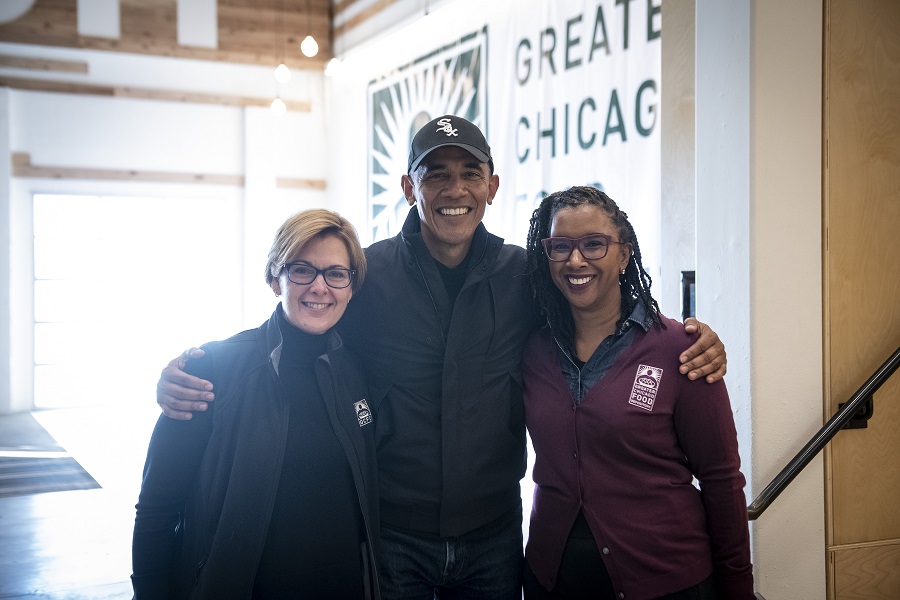

Ed Sunshine and Ann Connor, two of the founders of the Greater Chicago Food Depository, pose for a photo with Executive Director and CEO Kate Maehr.

Both Sunshine and Connor had worked in South America, feeding impoverished people in Peru and Chile – a revelatory experience for both of them. Upon returning to Chicago, they turned their focus to hunger in in the city. Sunshine researched and wrote a book called “The Hunger Handbook,” which listed all of the pantries in Chicago, while Connor pursued a master’s degree in social work.

Sunshine wrote the proposal for the Food Depository’s first federal grant of $47,500, which was awarded in March 1979 by the City of Chicago.

“We didn’t have a lot of resources, but we had many willing hands," Connor said.

"People stepped into the breach to move it forward,” she said. “It was the right idea at the right time in the right city.”

Each of the founders brought unique talents to the table. O’Connell was an insurance agent who came to understand food insecurity by talking with people in their homes and learning of their daily challenges. Snodgrass, an African-American woman who ran her own food pantry, was instrumental in engaging with black churches in Chicago.

“Gertrude was a force to be reckoned with,” Connor said. “She was a very bright woman who didn’t take no for an answer.”

Sunshine and Connor, now 80 and 81 years old, live in Miami Shores, Florida.

They still volunteer at their local food pantry.

“I’m really proud of what they’ve been able to do,” Sunshine said of the Food Depository. “I’m very happy that it’s helping all those people.”

On the move

As the Food Depository quickly grew in food donations and distributions, the idea of staying at South Water Market grew untenable. There were simply too many trucks going in and out.

In its first five years, the Food Depository would end up operating out of four locations in an effort to keep rent low or non-existent as the operations grew. Its next home: 6 North Hamlin, a historic building that once housed the Midwest Athletic Club in East Garfield Park.

An exterior shot of the historic building at 6 N. Hamlin in Chicago, where the Food Depository was briefly headquartered in the early 1980s.

Kranz chuckled as she recalled having to unload food donations through a regular-sized door in an alley. The food was stored around an Olympic-sized swimming pool, a vestige of the building’s past.

The next warehouse, located at the corner of the Peoria and Madison streets on Chicago’s Near West Side, had its own unique challenges. At times, the heat and the elevators didn’t work, Kranz recalled.

Despite such logistical challenges, the Food Depository was becoming less dependent on government funding as revenues grew. Tribune business columnist Bill Barnhart hailed the Food Depository as “one of Chicago’s brightest business success stories in recent years.”

Food Depository and community leaders pose at a 1984 ribbon cutting at the Food Depository's former home at 4501 South Tripp Avenue, the organization's fourth home in its first five years of operation.

But it became clear that the Food Depository needed more space in a better facility. In 1983, Kranz oversaw a $1 million campaign to move the food bank into a warehouse at 4501 South Tripp Avenue. Kranz had also been instrumental in lobbying state lawmakers to pass the Good Samaritan Food Donor Act in 1981, which limited liability for food producers that donated surplus to charities.

She departed the organization before that move took place in 1984.

In the winter of 2018, Chandler and Kranz visited the Food Depository at its current facility at 4100 Ann Lurie Place, reconnecting with the organization after many years. They liked what they saw.

“I saw the same kind of commitment to the mission as when we started, the same kind of passion and energy,” Kranz said. “It was really nice to see.”

Enter the brigadier general

In 1991, Brig. Gen. Mike Mulqueen was mulling retirement at 53, after a long, successful career in the U.S. Marines, when a head hunter called with a question: Would he like to run a food bank?

“I said, ‘What the (heck) is a food bank?’” said Mulqueen, 81, chuckling. “He came up and explained it.”

Mike Mulqueen, a Marine brigadier general, guided the Food Depository into the modern era in his tenure as executive director and CEO.

As executive director and CEO, Mulqueen effectively led the Food Depository into the modern era, implementing new systems and programs, and improving the overall organizational structure. He relished the professional challenge of bringing order to a charity in need of it at the time. And he developed a keen interest in accomplishing the mission.

“I realized that Food Depository’s basic mission of getting the food out is something you’ve got to do. You’re dealing with a daily disaster of hunger," Mulqueen said.

"I also figured out right away, where the Food Depository can contribute right away is to develop programs, training and education programs, that can lift people out of poverty,” he said.

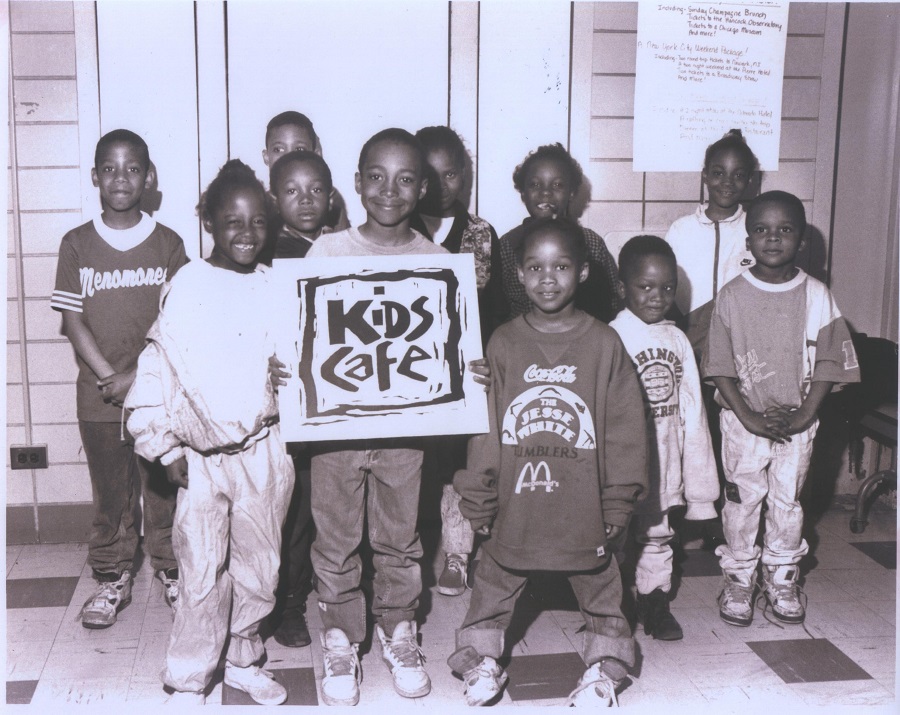

On Mulqueen’s watch, the Food Depository launched a produce program in partnership with Strube; Kids Cafe, a program that feeds children afterschool meals; Pantry University, a program designed to train pantry coordinators on best practices; and Chicago’s Community Kitchens, the 14-week culinary job training program that’s still going strong today.

An early photo of children in the Food Depository's Kids Cafe program, which began serving after-school hot meals for children in 1993.

Mulqueen only planned on leading the Food Depository for four or five years. Instead, he stayed for 15 years, largely to oversee the $30 million capital campaign to build a new facility. In the mid-to-late 1990s, the Food Depository’s programming and operations grew beyond the space available at the Tripp Avenue warehouse.

In the summer of 1999, Mulqueen appointed a young woman on his development team to be the new director of development, the person who would lead the charge on the bold fundraising campaign. Her name was Kate Maehr, only a few years out of grad school.

Mulqueen promoted Maehr with one of his trademark gestures: a finger gun and a wink. Maehr was shocked.

“This guy is a Marine brigadier general and he seems to think I can do the job,” Maehr recalled thinking at the time.

With the same gesture, Mulqueen would later tell Maehr that she was in his succession plan to replace him as executive director and CEO. He retired from the organization in 2006.

“For all the people who were able to lift themselves out of poverty, I’m really proud,” Mulqueen said. “It makes me feel good that the Food Depository is a much better organization than when I left. We did a lot of good and it’s doing even more good now.”

Evolving with the need

It would have been difficult to find a starker contrast from Mulqueen, at least on the surface.

Maehr, an Urbana native who studied English and art history as an undergraduate at Macalester College in Minnesota, later earned a master’s degree in public policy from University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Maehr, a mother of two young children at the time, was skilled at fundraising and passionate about social justice. But she was no brigadier general in the U.S. Marines, a persona that had come to represent the Food Depository in some ways.

“It was daunting, I’ll be honest with you,” Maehr said of the transition.

But soon after taking the helm at age 38 in 2006, Maehr was faced with some unique challenges that rendered the comparison largely irrelevant. She learned that food donations from reclamation centers – dented cans and the like – were in sharp decline. The Food Depository would need to buy more food to make up the difference, which would require significantly more fundraising.

That revelation led to an increased focus on consistently providing core items for pantries and expanding the Food Depository’s purchasing of fresh produce and proteins. If the Food Depository was going to buy more food, Maehr realized, it might as well buy the healthiest food possible.

In 2007, another alarming trend emerged: Reports from partner agencies across the network showed a spike in demand. The Great Recession hit hard, leading to massive increase in the number of Americans seeking food assistance. The Food Depository would need to grow even more to meet the need in the communities.

“I didn’t have time to worry about not living up to Mike,” Maehr said. “I was more worried about us not living up to what the community needed.”

In the years since the Recession ended, Maehr has worked to expand the Food Depository’s distribution of fresh, healthy food and initiated the organization’s focus on nutrition education. She’s also grown the advocacy department to protect and strengthen state and federal programs that help people facing hunger, and she’s worked to improve the culture both within the Food Depository and among the network of partner agencies.

President Barack Obama poses for a photo with Food Depository Executive Director and CEO Kate Maehr, at left, and Nicole Robinson, the Food Depository's vice president of community impact. Obama participated in a volunteer repack project at the Food Depository in November 2018. Photo courtesy of The Obama Foundation.

Maehr is now overseeing a large-scale campaign, called Nourish, to prepare the Food Depository’s facility and response to meet the changing needs of the community. Upgrades include a new volunteer area, renovated offices and expanded cold storage capacity for fresh food, among other improvements. In the years to come, the Food Depository plans to expand its job training programs and launch a new meal delivery service for older adults and people with disabilities.

In many ways, Maehr has helped the Food Depository recapture the passion and commitment of its founders for social justice, even as she leads the organization toward its future. The Food Depository will always be a food bank, but according to Maehr, it must be more than that, too.

Above all else, the Food Depository is a food justice organization, Maehr said.

Achieving the goal of ending hunger will require many willing hands, indeed. From the very beginning, the Food Depository’s impact has been a testament to the generous support and hard work of countless volunteers, donors, partners and advocates. Hundreds of food pantries, soup kitchens and shelters keep this dream alive every day.

“Just thinking about the people who had this idea and the people who still, every day, are making it happen – I find that fascinating, inspiring and something I wanted to be a part of,” Maehr said.

Share This Post