Every day after school, 13-year-old Ke’Meriell Hunter and dozens of other students trickle into a basement inside the Parkway Gardens apartment complex.

“I like the bond that we have down here,” said Hunter, a quiet, yet sociable eighth grader. This group of kids, she noted, has largely grown up together in the Future Ties after-school program.

“It’s like our own space. It just feels comfortable,” she went on to say. “Down here, you can be yourself.”

Hunter is one of an estimated 1,200 youth who lives in Parkway Gardens, a longstanding cluster of towering brick buildings that provides housing to hundreds of low-income families on Chicago’s South Side. For more than a decade, Future Ties has offered the community’s children nourishment, opportunity and a safe haven from the threat of gun violence that exists just outside their door.

Ke'Meriell Hunter, 13, and her mother Shaquita Wells at the Future Ties after-school program in Parkway Gardens. Wells is Future Ties' site supervisor.

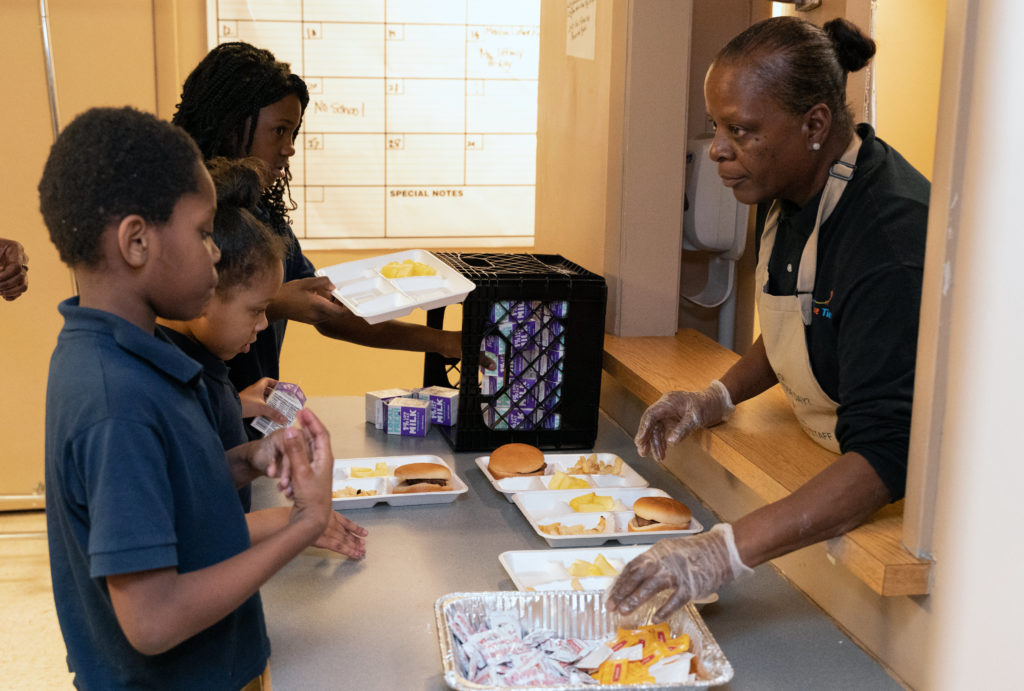

At Future Ties, about 40 students – who range in age from 5 to 13 – also receive a hot meal, thanks to an after-school meal program that’s offered in partnership with the Greater Chicago Food Depository.

Hunter's favorites? Chicken nuggets, diced pineapples and French toast.

“This may be the last meal that some of them may receive (in a day), and it’s a hot, nutritious one, which is important,” said Jennifer Maddox, Future Ties’ founder and director. “Just to have a hot meal on your stomach means a lot.”

A Future Ties student eats his supper, which is provided as part of an after-school meal partnership with the Greater Chicago Food Depository.

The stakes couldn’t be higher as Maddox and her team plan to expand the program to have more room and resources for older teenagers. A photo of teens on a past Future Ties field trip hangs on the wall. Two of the boys in the photo were recently shot, one fatally – 18-year-old Tyquan Manney.

“That was rough,” said Maddox, who is also a Chicago police officer, on how those events affected the other teens. “Many of them came here (following the shootings) just because they needed someone to talk to, just to get it off of them.”

A complex history

Parkway Gardens was once considered a model urban housing development.

In 1955, Parkway Garden Homes opened as the first housing development cooperatively owned by black Chicagoans. At the time, decades of discriminatory practices, including racial redlining, had led to a significant housing shortage among the city’s black middle-class communities. According to National Archive records, the project was praised in its era for being both innovative and affordable.

Notably, Michelle Obama lived there as a child in the 1960s. In 2011, Parkway Gardens was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the decades since, ownership of Parkway Gardens changed hands – to the federal government in the 1970s and then, in the 1980s, to private developers. The streets surrounding Parkway Gardens’ gates have changed, too, becoming notorious for gun violence.

Before opening the program 10 years ago, Maddox walked the grounds of Parkway Gardens as part of her patrol beat. Today, the Roseland native and 20-year Chicago Police Department veteran works in the department’s Office of Restorative Justice Strategies.

Jennifer Maddox, founder of Future Ties and Chicago Police officer.

“This may be the last meal that some of them may receive (in a day), and it’s a hot, nutritious one, which is important. Just to have a hot meal on your stomach means a lot.”

– Jennifer Maddox

In 2010, Maddox founded Future Ties after noticing a need among the complex’s youth. Maddox’s goal was – and still is – to offer not only a comforting place that keeps kids away from trouble, but to also be a resource for parents who need additional support while they work or go back to school.

“It takes a village to raise a child, and this program does just that,” said Shaquita Wells, Future Ties’ site supervisor and Hunter's mother. “Our kids are going off to college, we’ve got kids that went into the military. They’re doing something with their lives.”

The mission is personal for Maddox. Now 48, she was a teenage mom and struggled at times to take care of her two sons. Maddox still holds on to an old public aid card from her teenage years and shows it to parents to symbolize how she’s been in their shoes.

“I bumped my head against the wall many times just trying to figure it out,” said Maddox. “I said if I ever got a position where I could give back and help, that’s what I would do.”

Expanding the reach

On a recent afternoon, children wearing their school’s uniform of khaki pants and navy blue shirts bounded into Future Ties with a familiar question: What are we having to eat?

Lavern Short serves supper to the kids at the Future Ties after-school program

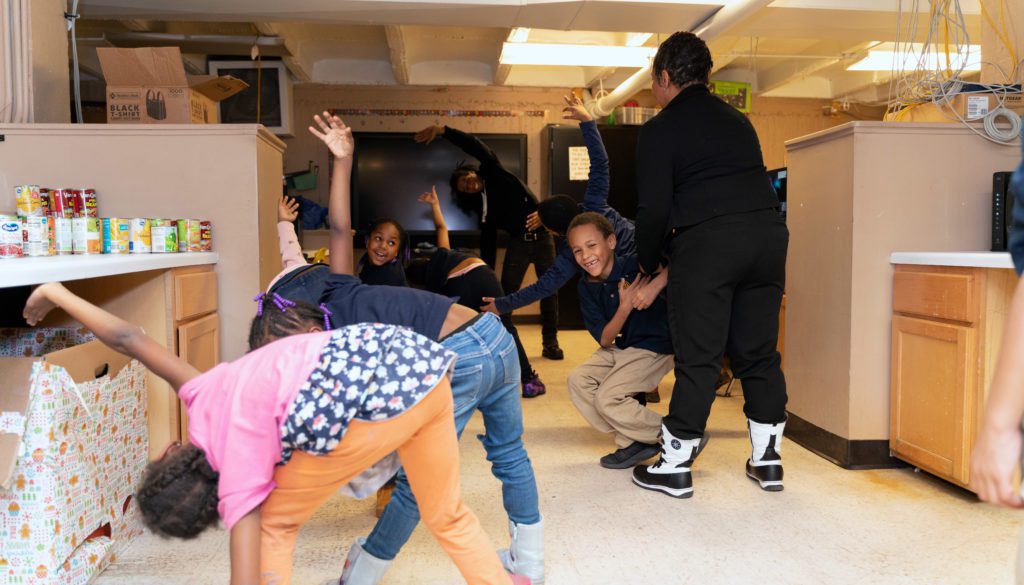

Hamburgers, fruit and milk was the menu for that particular day. Lavern Short, 60, flipped burgers on the griddle and welcomed the children as they approached the kitchen. After eating and settling in, the kids were led in some stretching and group meditation before starting on homework and breaking into other structured, educational activities.

A young boy drinks the milk served during supper at the Future Ties after-school meal program

Later, Short played Go Fish with some of the younger children.

“I love being around the kids. It seems like we’re keeping them off the streets,” Short said. “Some of them start off rough and you have to win their trust.”

In recent years, Maddox said she’s seen some positive improvements in the area, which she credited to local investments that have led to job growth and other resources. Many people who live outside the complex tend to only focus on the negative things that they see, Maddox said, when in fact, many loving families live within.

Lavern Short, who served supper to the Future Ties students, joins them for a game of Go Fish.

But Maddox knows there’s still work to be done. She plans to expand her organization, with hopes of taking over an adjacent building in the complex.

“We need them folks, right there,” she said as she pointed to a photo of a group of teenagers taped to the wall. The teens aged out of Future Ties’ school-year programming, but still need a safe place to eat, do homework, hang out with friends and join recreational activities.

The kids at Future Ties stretch and meditate together before breaking into their homework and other after-school activities.

Maddox also envisions offering counseling services in the new facility. By the time they reach their teenage years, many of the youth have already experienced trauma.

She has made a promise over the years to the children of Parkway Gardens – a promise to give them a place where kids can just be kids. She intends to keep it.

“I want to see it happen for them,” she said.

Share This Post